Within the space of a month, Africa experienced two extraordinary cable disruptions that led to internet outages in at least 11 countries across the continent.

In February, three cables were severed in the Red Sea by an anchor drag, while on 14th March an undersea canyon avalanche incident off the coast of Cote d’Ivoire led to damage on four cable systems – WACS, MainOne, South Atlantic 3 and ACE. The scale of this disruption was unprecedented; with seven cable systems affected at the same time, there were naturally widespread internet issues for days across many markets. However, the response from service providers was immediate and connectivity was largely restored within around ten days.

Guy Zibi, Founder of Xalam Analytics, says that this underlines how resilient Africa’s internet infrastructure has become. He notes that if this incident had occurred ten years ago, key parts of the region would have had no internet access; while there was disruption in terms of the quality of usage during this event, blackouts were not widespread.

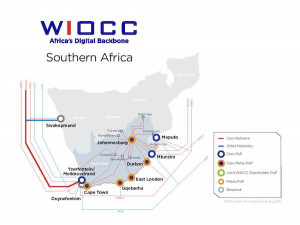

Some countries were worse affected than others, but this was due to the configurations of cable traffic usage. The SAT-3, WACS, ACE, and MainOne cables run along the West Coast, and so their simultaneous failure had a strong impact on countries like Cote d'Ivoire and some of the smaller economies on the West Coast. There is more diversity of routes on the East Coast, which meant that despite the disruption of the three cables in the Red Sea, it has been possible to diversify traffic through international cables running through Djibouti.

The West Coast incident saw the four affected cables taken out in turn. Since they are laid at depths of up to 2.4km to 4.5km below sea level and at least 100km apart, it is essentially impossible that human activity was to blame; the most likely scenario is an undersea avalanche of debris travelling several hundred kilometres from the shore going out to sea. This is supported by the fact that the Equiano cable – which lies much further offshore - was unaffected by the incident, notes Chris Wood, CEO of WIOCC Group - the parent firm of infrastruture provider WIOCC. Laid in 2022, the cable went live last year and played a huge role in safeguarding the resilience of Africa’s connectivity during this incident.

“WIOCC owns a fibre pair on Equiano, so our network didn't go down because we had redundancy across five systems”, notes Wood. “This enabled WIOCC to restore other networks on Equiano across the next few days. A lot of the carriers that were really impacted, that caused the internet outages in West Africa, didn't have the capacity on Equiano. Within around five days of the cuts, WIOCC had lit around 2.5 terabytes of capacity, adding over 100 circuits into the network and restoring around 30 different operators’ networks in the region. Some of that traffic went north to Europe, and some of it went south and connected into WIOCC’s IP network in South Africa, which is why the impacts were limited in terms of time.”

Wood notes that the scale of the outages is unprecedented in Africa. The affected systems have never all been hit at the same time – and the issue was compounded by the cut cables in the Red Sea, as it would normally be possible to restore East traffic on the West and vice versa. Having cuts on both sides of the continent has resulted in traffic being pushed onto Equiano – which in turn is risky, as if anything were to happen to this system, the situation could be disastrous. Zibi notes that laying cables further offshore should be a key takeaway from this incident – although he acknowledges that this is difficult in the Red Sea as it is a geographical bottleneck. Increasingly cable projects are taking alternative routes to avoid this, such as running terrestrially through Saudi Arabia and back to the Mediterranean via Jordan.

The launch of the 2Africa cable later this year will add further resilience and redundancy, but operators will need to purchase capacity on the new systems. Wood argues this is in their interest: “What this has shown is there's no such thing as too many systems. [Providers] need to have capacity on whatever systems are available. People often talk about…[whether] these new cables create an oversupply of capacity [in Africa] – it’s not about the volume of capacity that the cables can carry, it’s the number of cables that you have which is important. Having that level of redundancy spread across multiple cable systems leads to a much more stable network.”

The incident has raised questions about whether Africa is overly reliant on subsea cable connectivity. According to Zibi, the answer is yes – but he argues that the global internet infrastructure is underpinned by subsea cables, and highlights the more pressing issue of Africa’s overreliance on international traffic in its internet infrastructure. He notes that there has been progress on this front, with the Internet Society working towards having 80% of African internet traffic being exchanged locally as opposed to going through Europe or the Americas. In some markets, such as South Africa and Nigeria, the 80:20 ratio has been achieved – this percentage of traffic stays local in some form, so if there’s a disruption of this nature, the impact is lessened as most of the traffic was local to begin with. There are plenty of countries that have not achieved the ratio, and they are still vulnerable to this type of disruption in the international capacity segment, but it’s moving in the right direction. “I suspect that in in five to ten years, this type of disruption will just be a little blip on the radar, because you'll have more diversity, you’ll have bigger sized cables, you'll have a lot more hosting capacity. Some of this will still be felt, but relatively minimally”, says Zibi.

Both the scale of the outages and the nature of the disruption are impacted by overreliance on the international transit base. Certain cloud providers were more affected since their architecture was more reliant on the cables in place, and Zibi says that the key lesson is to diversify, whether that’s cables, providers, routes, international capacity, or using terrestrial fibre. He notes that this adds additional resilience, as a disruption on the West Coast can be rerouted to the East cost terrestrially via fibre, then connected to one of the international cables back to Europe. Such configurations are now being put into places as a failsafe, but more investment is required.

Wood agrees that terrestrial networks will see an uptick as companies assess how they architect their networks. “People will look at terrestrial fibre solutions to get from one country to another cross-border, then you come out to a landing station of a different country. Quite often, cable cuts happen close to shore, on a branch coming off a main trunk into an individual country - so if that branch gets cut, you're out. People are going to be looking at terrestrial connectivity as well to get between landing stations and then have diversity.”

Zibi notes that the upcoming launch of the 2Africa cable will ameliorate the situation, adding that since the system’s constituent pieces are ‘semi-independent’ it can be ‘self-healing’ – plus the size of the cable will help to bring down prices, which is a major consideration if connectivity providers increasingly need to hold capacity across four or five different routes. Today, the average provider has capacity on two to three routes – this must double, but that will require bandwidth costs to come down. While this process has begun, prices need to fall further.

ISPs will of course baulk at having to double their number of suppliers for capacity, and since ARPU in Africa is on the lower end of the global scale, cable providers are aware that they can’t gouge their customers by overselling capacity. Zibi notes that pricing is an area of concern – in theory, with more capacity, there will be greater supply and so prices will fall. And while average unit costs of deploying and delivering capacity are falling, the wholesale market is relatively low margin compared to other segments of digital infrastructure, so it’s challenging for providers to cut their prices.

There are not many options that are financially viable for ISPs to build resiliency into their architectures. Satellite cannot deliver enough capacity and would also be far too expensive – it can be used for backup for certain applications, but the volume of capacity it can deliver is a fraction of that of a subsea cable. Wood notes that WIOCC lit two and a half terabytes of capacity in five days; even a satellite system such as Starlink, across the entire constellation can deliver only a few hundred gigabits to one location.

“You wouldn't be able to restore Africa's internet on satellite - you can use it for certain specific applications, but it's not a replacement or a redundant solution for submarine cables”, says Wood. “Is the answer more cables? Potentially, but they are very expensive - to lay a new cable from South Africa to Europe, picking up four or five countries on the way, is about a billion dollars…are the end users willing to pay collectively another billion dollars for a bit of extra redundancy? Even if [they are] it's still a seven-to-ten-year process to start sorting the funding, design the system, lay the system, and commission it - so there's no quick fix to this.”

Even with the additional capacity of Equiano and 2Africa, Zibi believes that more cables will be required – particularly as some of the existing cables, such as Sat-3, are past their useful lifespan and will be decommissioned in due course. He estimates that the West Coast should be served by at least another one or two large cables, as this would enable more local hosting capabilities for internet exchanges, data centres and cloud applications, making it easier to mitigate the impacts of future cable outages.

As Wood notes, the world’s internet runs on subsea cables - there is no viable alternative for running multi-terabit solutions around the world. Satellite can do certain things, but it can't run the internet, which requires thousands of terabytes globally. While Africa’s reliance on subsea cables is perhaps more pronounced than other regions, this incident has demonstrated the extent to which the continent’s connectivity has become more resilient over the past ten years. The next steps are also clearer – a shift towards exchanging more internet traffic locally, and deploying future cable systems further offshore to safeguard against such incidents. The impending launch of the 2Africa cable system will deliver further redundancy, and as additional routes are added, prices should fall, meaning ISPs have more affordable options to shore up their resiliency.